‘Disappointing take on an interesting man’, Honest History, 30 August 2016

Kristen Alexander* reviews Mark Baker’s Phillip Schuler: The Remarkable Life of One of Australia’s Greatest War Correspondents

Phillip Schuler was a journalist working at Melbourne’s Age newspaper when the Great War erupted. He hoped to be appointed as Australia’s official war correspondent but that role went to Charles Bean. Undeterred, Schuler decided he would report the war anyway and so the 26-year-old embarked for Egypt with the AIF’s first convoy in November 1914.

Without official status, Schuler did not have the same access to action and troops afforded to Bean. Denied entrée to Gallipoli, he turned his attention to the wounded haemorrhaging from the peninsula. Moving freely between hospital ships, his senses were overwhelmed. His despatches were direct and passionate; his anger and shock were obvious. He lay blame where appropriate but also praised the brave stoicism of the wounded as they faced death. Subject to censorship, his despatches, however, failed to gain an immediate readership. One, for instance, filed from Alexandria on 15 July 1915, was not published by The Age until 16 October. Despite the delayed publication, the despatches proved influential.

Without official status, Schuler did not have the same access to action and troops afforded to Bean. Denied entrée to Gallipoli, he turned his attention to the wounded haemorrhaging from the peninsula. Moving freely between hospital ships, his senses were overwhelmed. His despatches were direct and passionate; his anger and shock were obvious. He lay blame where appropriate but also praised the brave stoicism of the wounded as they faced death. Subject to censorship, his despatches, however, failed to gain an immediate readership. One, for instance, filed from Alexandria on 15 July 1915, was not published by The Age until 16 October. Despite the delayed publication, the despatches proved influential.

Just as Schuler was filing the medical despatches, he heard that he had been endorsed to report from Gallipoli. He arrived in late July and was in prime position to cover the August offensive. Again, it was some weeks before Australians read his despatches; his account of the early August action did not appear until 28 September 1915, after his departure from Anzac Cove. He was back in Australia before the last of the Australians had been evacuated, working on a more permanent record of the conflict.

Despite the official constraints, Schuler made the most of his stint as an unofficial correspondent. He took thousands of photographs which would later form an important pictorial record of the war and The Battlefields of Anzac, an illustrated booklet published in March 1916, and Australia in Arms both contributed significantly to the formation of the Anzac legend. By the time the latter book was released in late 1916, Schuler, who had enlisted with the AIF in April, had embarked for France as a driver with the 3rd Division’s Divisional Train. He was seriously wounded at Messines, Belgium, on 23 June 1917 and died later that day.

Mark Baker, as a journalist who has covered Australia’s late 20th century wars, understands Schuler’s work and has devoted many years to discovering the correspondent’s life and analysing his reportage. Baker writes well and makes good use of his secondary source material to establish a readable, flowing narrative which sets the military context in which Schuler operates. Sadly, given Schuler’s career as a writer, he seems to have left very few written traces of personal life and this creates a significant biographical gap. Details of Schuler’s love affairs – and the child about which he knew nothing – come mainly from forensic research and family interviews.

With no diaries to illuminate Schuler’s motivations and personal responses, and so few published despatches, Baker draws heavily on Australia in Arms, often quoting large extracts. To help fill the gaps in the personal story, Baker mines the records of those who knew Schuler professionally, such as Charles Bean and General Sir Ian Hamilton. Rather than recast their assessments or descriptions, however, Baker again quotes lengthy extracts.

So slim is the personal primary evidence that Schuler does not appear in every chapter and, in some, is all but absent. In Chapter 9, for instance, Schuler is mentioned in passing just twice and, in a third reference, his opinion is substantiated by citing Bean. Baker compensates for Schuler’s lack of presence by ‘padding’, such as describing action at Gallipoli even after Schuler’s departure. Even people with only peripheral connections to Schuler or events surrounding him are included, such as Lieutenant Colonel Maurice Hankey. While it could be argued that Hankey had to be mentioned because he defended accusations of Hamilton’s weak leadership, much of the background detail could have been omitted, as could Hankey’s reunion with his cousin, Major Carew Reynell – who had nothing to do with Schuler – Reynell’s background, noted military antecedents, brief Gallipoli career, and death.

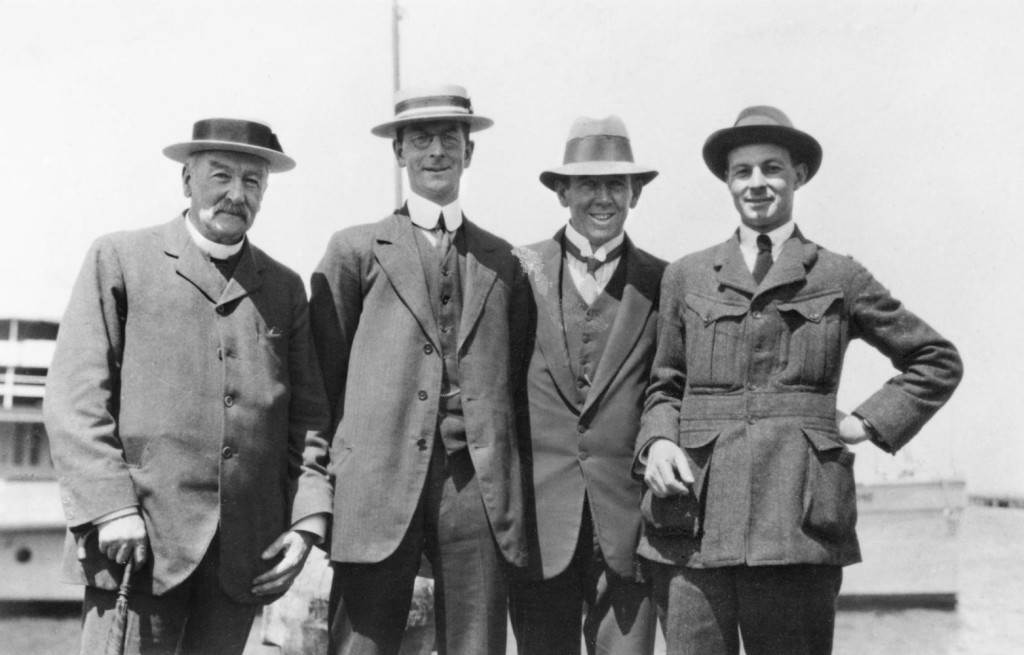

Edwin Bean (father of Charles), Charles Bean, Archie Whyte, Age editor, Schuler (National Anzac Centre/AWM A05379)

Edwin Bean (father of Charles), Charles Bean, Archie Whyte, Age editor, Schuler (National Anzac Centre/AWM A05379)

Biography is a difficult genre; many authors struggle to remain dispassionate about their subject. Baker clearly admires Schuler and his work is imbued with a keen empathy for Schuler, his struggles to gain accreditation and his reactions to what he sees. This is understandable and excusable. What is less justifiable is the apparent bias against Keith Murdoch. For example, in Chapter 11, entitled ‘The Letter’ – a chapter in which Schuler barely appears – Murdoch and his Gallipoli letter are savaged. The prejudice continues throughout, on occasion verging on the vindictive.

Allen & Unwin’s publicity material proclaims this as the ‘definitive biography’ of Schuler. Perhaps it is, but it is a slight one. In fact, given the amount of space devoted to Bean, Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett, Keith Murdoch and their coverage of conflict on the peninsula, the book should have been promoted as a ‘life-and-times’ account, or ‘The Story of Four Journalists at War’. If you take out the partiality and padding as well as the detailed references to the other three correspondents, this would have made an engaging Wikipedia entry (there isn’t one at the moment).

As a book-length biography of a man who had a key role in shaping the Anzac legend Phillip Schuler: The Remarkable Life of One of Australia’s Greatest War Correspondents disappoints, especially when compared with Peter Rees’s magisterial Bearing Witness: The Remarkable Life of Charles Bean, Australia’s Greatest War Correspondent, also published by Allen & Unwin. (There is perhaps some irony in the similarity of the sub-titles. Or maybe just carelessness. HH)

* Kristen Alexander is an Australian writer, author, bookseller and PhD candidate at UNSW Canberra. She also reviewed the Beyond Surrender collection on Australian POWs. Her book, Taking Flight, on aviator Lores Bonney, was reviewed on Honest History.