Update 28 September 2017 updated: War Memorial Director Brendan Nelson at the Press Club: speech or performance art? Polygon Wood ‘remembered’

We said (21 September, below) we would look more closely at Dr Nelson’s 19 September National Press Club speech ‘Tragedy and triumph – 1917’. This followed our earlier extensive analysis of his speeches, and our polite challenge (Update of 25 July) to him to break new ground at the Press Club rather than deliver more of the sentimental rhetoric common in his earlier outings.

Australian stretcher-bearers trapped in mud, Ypres, 1917 (World Socialist Web Site/Great War Project)

Australian stretcher-bearers trapped in mud, Ypres, 1917 (World Socialist Web Site/Great War Project)

The 19 September speech was about Passchendaele and Beersheba. It was not televised but it played to a full house, received a standing ovation, and reduced the speaker himself to tears (39 illustrations).[1] Our first quick skim of the text of the speech led us to say ‘Same old stuff’. This snap judgement was a touch harsh – but not much. The text of the speech is here, along with more speeches by Dr Nelson and others.[2]

On the positive side, the speech goes hard on the horror and futility of Passchendaele (although the long quotes are mostly not sourced), brings out the tension of that hot desert evening outside Beersheba before the charge, and deals with the impacts of war deaths on families. It even has a passing mention of divisions at home (the Great Strike and the second conscription referendum) and in Russia. It recognises – if only as a footnote, when domestic events were central to Australia’s war experience – that there was more to Australia’s war than blokes in khaki going over the top and dying bravely.

Dr Nelson even touches briefly on the ‘was it worth it?’ question, admitting that all the ground ‘won’ at Passchendaele was lost within five months, though which empire controlled a few acres of blasted dirt was probably not how that key question would have been framed by the families of the dead. When he imagines two bereaved mothers asking ‘why?’, Dr Nelson has the answer that these mothers’ sons died ‘for a better world’ and ‘the love of friends’. Alison Broinowski and I pointed in The Honest History Book to Dr Nelson’s tendency to ‘spout the same glib commemoration-speak that was common for warmongering politicians and bloodthirsty clergymen a century ago’ (page 5).

As often in his speeches, Dr Nelson overclaims (at the end of the Great War, ‘We had our story. We were Australians’), insists that the War Memorial contains ‘sacred relics’, can’t resist some of his standard locutions (‘free and confident heirs’, ‘the broad brushstrokes of history’, ‘awkward humility’, ‘truths by which we live’, ‘For we are young, and we are free’), and falls back on a hackneyed CEW Bean cliché – this time, the dying soldier hoping that people in Australia will remember him.

Dr Nelson concludes with the claim that Australians ‘emerged [from 1917] with a greater belief in ourselves and a deeper understanding of what it means to be – Australian’. People who want a more balanced verdict than that could read Joan Beaumont’s Broken Nation or Peter Stanley’s The Crying Years.

On the morning of 19 September, Dr Nelson discussed the themes of his imminent speech with Alan Jones on 2GB. Spruiker and shock-jock agreed on most things and Jones called Nelson ‘a star’. Dr Nelson’s term at the Memorial has indeed seen praiseworthy innovations (the Holocaust exhibit being the most notable) but his speeches have been innovative not so much in their content (more emotion than evidence) but in their mode of delivery – more scatter-gun than structure, more sermon than speech, more performance art than oration. We are sorry we missed this one, though we have read the text very closely.

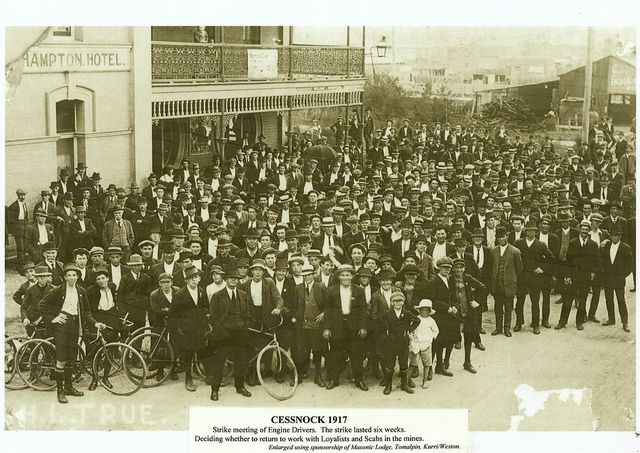

Striking engine drivers, Cessnock, NSW, 1917 (World Socialist Web Site/Coalfields Heritage Group)

Striking engine drivers, Cessnock, NSW, 1917 (World Socialist Web Site/Coalfields Heritage Group)

While the 19 September effort obviously tugged at the heartstrings of those present – there was a standing ovation, after all – it also brought to mind the strictures of philosopher Raimond Gaita, writing in the latest issue of Meanjin about ‘truth in the time of Trump’. ‘To think well’, says Gaita, ‘ we must … develop an ear for tone, for what rings false, for what is sentimental or has yielded to pathos and so on’. Without such a sensibility ‘we are easy prey for demagogues’. It is imperative also to be able ‘to distinguish … grief from maudlin self-indulgence’.[3] Indeed.

Gaita’s distinctions remind us in turn of a 2015 conversation between historian Joan Beaumont and journalist Kate Aubusson.

I [Aubusson] told Professor Beaumont about weeping over the grave of my great, great, great uncle. She said “if what you feel is grief, we need another word to describe what the war widows and children felt in 1918”.

What my generation experiences as “grief” is not grief so much as a learnt nationalistic sentimentality based on myth far removed from the reality of that visceral, horrendous experience and the repercussions for those who lived through it.

Meanwhile, in a rather different style of commemorative event, at the Polygon Wood Dawn Service in Belgium (full video), there were speeches from Minister Tehan, the Governor-General, Princess Astrid of Belgium, and others. Fairfax ran some contemporary stories from CEW Bean. The Australian had historian Ross McMullin on ‘Pompey’ Elliott. The Parliamentary Library did a background paper. Fiona Carruthers in the Australian Financial Review spoke afterwards to officials. Historian Matthew Haultain-Gall explained why Polygon Wood is not better known, suggesting that the relative lack of success in the 1917 battles made them less susceptible to being remembered, compared with the ‘nation-building’ at Gallipoli and the ‘victories’ of 1918.

Notes

[1] The original Inside Canberra post was headed ‘Dr Brendan Nelson fights back tears at the National Press Club’. The fixation on tears is reminiscent of ABC TV coverage of the Director’s previous speeches at the Press Club. The cameras seek out signs of tears, as if being seen to be ‘moved’ is the point of the occasion.

[2] Of the 36 speeches since May 2016, 23 are by Dr Nelson. Of the clickable ‘thumbnails’ leading to the text of these speeches, 19 of 23 carry a picture of Dr Nelson, 15 of them on his own.

[3] Raimond Gaita, ‘The intelligentsia in the age of Trump: reflections of truth and truthfulness’, Meanjin, 76, 3, Spring 2017, pp. 41, 43.

[4] The author has often been moved to tears while giving speeches about death and suffering in war but he believes that is not the point. The point is to ask questions about war and to encourage others to do so, too. The author’s 2013 visit to the Tyne Cot cemetery is reported here.

Update 21 September 2017: ‘Life to its top’?: the Australian War Memorial reflects on World War II; Peacekeeping memorial; Lest We Forget Ute Me Gong ‘Straya

‘Life to its top’?: the Australian War Memorial reflects on World War II

The Memorial has recently opened a new exhibit, Reflections: Honouring our Second World World War Veterans. The exhibit is located in a circular alcove within the World War II galleries and on the Memorial’s website. It consists of large colour still photographs of men and women who served in the war. Scrolling through the photographs on the screen takes 18 hours as there are 6500 people, shot by 450 photographers over two years. Many of the subjects wear their medals, some of them also have RSL, AIF and other badges.

On the wall there is a brief description of the war. The concluding paragraph says, ‘The war touched all Australians, and changed the nation. Those who served and those who died are remembered here. Lest we forget.’ (On the day we visited, the ‘g’ out of forget had fallen out and was lying on the floor. We attributed this to a lack of glue rather than symbolism, and returned the fallen reverently to an attendant.)

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr (1841-1935) at about the time his heart was touched with fire (Wikiquote)

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr (1841-1935) at about the time his heart was touched with fire (Wikiquote)

The exhibition is a worthy effort to present the faces – and, on the website at least, the names – of those who are left of the men and women who went to this war. One would have liked to know more about their lives after the war also: the lines on those faces surely cannot all be attributed to war service.

‘We have shared the incommunicable experience of war’, famously said Oliver Wendell Holmes, ‘we have felt, we still feel, the passion of life to its top. In our youth our hearts were touched with fire.’ Is that the idea here? Yet not even Holmes, the romantic war spruiker, would have claimed his war experience was the touchstone of his life, next to which everything else paled. These pictures carry that implication: that the subjects’ few years of war service – not their families, not their children, not their hard and worthwhile civilian work, not the full lives they lived and the people they loved and who loved them – is what we should most remember about them.

It is ironic that the space the new exhibition has taken up was previously occupied by a small display depicting the early post-war years. The display covered the Korean War, the development of new suburbs, the growth of prosperity, industrial development, and immigration. It gave some hints about what happened next to the men and women of World War II. Reflections just gives us those lined faces.

Peacekeeping memorial

As we foreshadowed, the memorial was unveiled last Thursday, with speeches by the Governor-General and Minister Tehan. ‘Peacekeepers’, said the Governor-General, serve ‘not in the name of conquest or self aggrandisement, nor in the name of parochial national self-interest. They do it, in the name of compassion and humanity. In the name of what is right.’

Planning committee chair, Major General Tim Ford, said of the memorial design, ‘As you move through the memorial monoliths through a passageway of light, the idea is the peacekeepers are keeping apart the warring forces and providing the hope’. Well done to the people who worked for 12 years to bring this necessary project to completion.

Peacekeeping memorial, Anzac Parade (Peacekeepingmemorial)

Peacekeeping memorial, Anzac Parade (Peacekeepingmemorial)

Lest We Forget Ute Me Gong ‘Straya

Honest History has been meaning for some time to note the varied facets of Lee Kernaghan OAM, bush balladeer and Stetson wearer. Mr Kernaghan a couple of years ago with other singers brought out a video ‘Spirit of the Anzacs’, with proceeds to charity. In recognition of his charity work, Mr Kernaghan was awarded an Order of Australia Medal in 2004 and was Australian of the Year in 2008.

‘Spirit of the Anzacs’ promo (Twitter)

‘Spirit of the Anzacs’ promo (Twitter)

Broadening the focus, also among Mr Kernaghan’s oeuvre is the official video for the Deniliquin Ute Muster, titled ‘Ute Me’ (2012). The lyrics are here.

‘Ute Me’ video (Youtube)

‘Ute Me’ video (Youtube)

In 2015, when the extreme right group Reclaim Australia, without permission, used Mr Kernaghan’s music, specifically ‘Spirit of the Anzacs’ at its rallies, Mr Kernaghan said the use of his work should be ‘ consistent with – and respectful of, the memory of … [soldiers who] laid down their lives for the freedoms we have today’. (More; more still.) His response was seen by some commentators at the time, however, as less forthright than that of other artists, such as Midnight Oil, whose work had also been used by Reclaim Australia. These artists explicitly demanded their work not be used.

Directorial disappointment

Back in July, we noted that the Director of the Australian War Memorial, Brendan Nelson, was to speak this week at the National Press Club. His subject was Beersheba and Passchendaele 1917.

We pointed out that the Director’s speeches were renowned for their sentimentality and repetition. We hoped, however, that the Press Club speech might foreshadow some bold new directions, carrying on from the Memorial’s new Holocaust exhibit (recognising that wars affect people other than Australians), its sideways steps towards acknowledging Indigenous Australian warriors defending country on country (as well as overseas while wearing the Queen’s uniform), and the possible exhibition on the aftermath of the Great War (showing that war is not just about blokes in khaki doing and dying).

The speech duly happened on Tuesday, 19 September, but we were unable to attend and it was not televised. Disappointing. We’ll post a link to the text of the speech when it is available – and perhaps some analysis. (STOP PRESS late Wednesday: The speech has just appeared on the Memorial’s website. A quick skim evokes the comment, ‘Same old stuff’, but we’ll look more closely and get back to you. Sounds like disappointing again.)

Centenary Watch archive