‘Britain, Australia, New Zealand, SEATO, the secret war in Laos, and counter insurgency expert Colonel “Ted” Serong’, Honest History, 13 June 2017 updated

Australia’s war in Vietnam has been relatively well documented. Less is known, however, about what happened in and around the also war-torn neighbouring country of Laos. Willy Bach’s Master of Philosophy thesis, ‘Collaboration of Britain, Australia and New Zealand in the Second Indochina War, with particular focus on Laos, 1952-1975’ (University of Queensland, 2016) does much to fill in the gaps.

Willy Bach’s articles on Agent Orange in Vietnam and the Long Tan anniversary were posted in Honest History, as was his poem ‘Anzac-ed out 2015’. Willy also did some essential research for us in the Queensland State Archives. He also blogged.

Willy Bach (UQ)

Willy Bach (UQ)

In November 2016, Willy sent us a copy of his thesis ‘[i]n the hope that [it] could be a useful resource from which to borrow freely’. We were pleased and honoured to receive the thesis but, due to commitments with The Honest History Book, our borrowing had to be put off for some months.

In late 2016, Willy accompanied his partner, Rowan, to Cambridge, UK, where Rowan was to do research work. Willy had been ill at times while working on his thesis, and his condition worsened this year. (Willy died on 27 June. Honest History sends condolences to his friends and loved ones.)

Willy’s interest in the matters covered by his thesis began in 1966, when he was a sapper in the British Army, working on Operation Crown, the construction of an airfield near the town of Leong Nok Tha, North-East Thailand (a 2002 ABC program on this, with interview with Willy). In the thesis Acknowledgements, Willy says this:

I will always remember that while I was working on the Leong Nok Tha airfield in 1966, there was also a Thai civilian crew of labourers who sang and banged gongs on their way to work, as they carried their lunches in tiffin carriers. They were dignified. I had never seen people sing their way to work. It reminded me to dedicate this thesis to all who were harmed and disadvantaged by what we were doing.

Willy’s Bach’s friends are having his 134-page thesis professionally edited for publication as an e-book. In the meantime, Honest History is pleased to publish some extracts. Chapter 3 of the thesis, on Agent Orange, covers similar ground to the article we published in 2015 (link above).

Honest History believes Willy Bach’s thesis makes an important contribution to the history of Australian and Commonwealth involvement in South East Asia in the 1960s and 1970s, particularly because of Willy’s use of declassified official documents and of secondary sources in specialist publications. Honest History has made pdfs of three extracts from the thesis:

- Operations in Thailand and Laos 1962-68 (pp. 13-24);

- Australia, SEATO and Laos (pp. 25-39);

- Australian Colonel FP (‘Ted’) Serong and counterinsurgency in Vietnam (pp. 54-59).

Background

To put these extracts in context, we have reproduced below the Abstract of the thesis (pp. i-ii), the first few pages of the Introduction (pp. 2-7) and the Summary (p. 12). These pages indicate both the nature of the problem dealt with by the thesis and the extent to which – and perhaps reasons why – this history has not been explored previously. (We have added a couple of illustrations and turned footnotes into endnotes.)

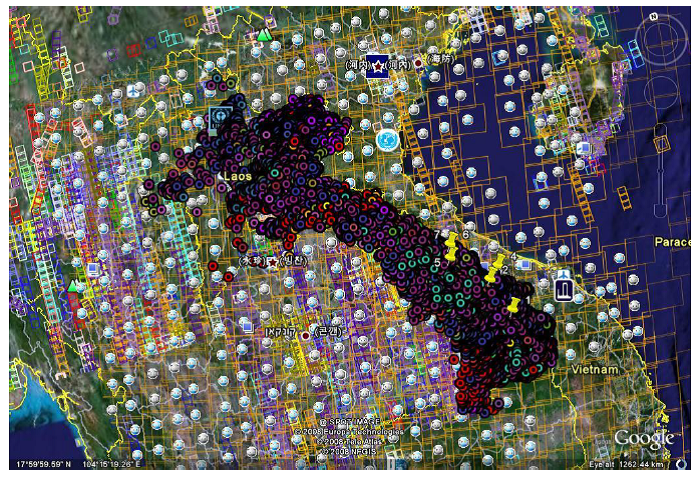

Cluster bombs dropped on Laos during the period covered by the thesis

Cluster bombs dropped on Laos during the period covered by the thesis

[p. i]

Abstract

This thesis examines the collaboration of Anglosphere allies, Britain, Australia and New Zealand in the US-led Indochina War and in particular, the Secret War in Laos 1954-1975. Though called the Vietnam War, and the American War by the opposing side, it was a regional war that affected all neighbouring countries. The war affected these Anglosphere allies too, whilst undermining their democratic institutions. The history of this collaboration has been largely ignored or denied, as the hitherto scarce literature showed. Most of the literature about the war has been written by US authors, or focuses on what the US did in promulgating the war. The actions of SEATO allies, Britain, Australia and New Zealand have been largely overlooked. This gap in the historical record needs closer examination. Three aspects of this collaboration have been selected to demonstrate its extent and depth.

The thesis examines the building of the Operation Crown airfield near Leong Nok Tha and the Post Crown Works road networks in Thailand over the 1962-68 period, and the rotation of many engineer units and support services from Britain, Australia and New Zealand. This infrastructure was part of the US-led SEATO military build-up in Thailand. Crown was also used for commando incursions into Laos across the Mekong River. Participation in the SEATO alliance included staffing of the SEATO Headquarters in Bangkok; planning of an invasion, occupation and partition of Laos; and planning and participating in major SEATO exercises designed to rehearse the intended invasion. The plans also involved Britain contributing nuclear weapons. The invasion was eventually abandoned due to the divergent views, limited commitment of SEATO allies, and the US failure to consult.

The study also describes Britain and Australia’s provision of counterinsurgency warfare advisers and how these individuals worked with special forces, mercenaries, and ethnic minorities to carry out covert warfare. These Anglosphere advisers also provided the US with strategic advice based on Britain’s experience in Kenya and Malaya. These counterinsurgency activities included ‘Hearts and Minds’ projects, but also the coercive removal of civilians from their traditional ancestral farming land. They set up strategic hamlets and refugee camps, destroyed food, crops, domestic animals, homes and property, and carried out the interrogation of prisoners. Eventually, advisers from Britain and Australia joined the leadership of the Phoenix Program, which assassinated 20,000 to 30,000 suspected communist sympathisers in South Việt Nam.

The third aspect of Anglosphere involvement in the war detailed here is the process of invention and development, and eventually manufacture of defoliants – including Agent Orange – that were of great importance to counterinsurgency warfare. The destruction of food crops was as central to the US Ranch Hand program as the removal of forest canopy to reveal the disposition of their

[p. ii]

adversaries. Defoliants were used to coerce civilians to vacate their homes and farms, turning these areas into free-fire zones. The toxicity and teratogenic nature of these chemicals caused aborted foetuses and unviable deformed babies. Eventually, the US government was obliged to phase out defoliant use, beginning with the immediate ending of crop destruction in 1971.

The British, Australian and New Zealand contributions to the war were a whole of government undertaking. There were connections between the ‘big’ conventional war that included massive bombing and invasion plans, as well as the ‘small’ covert unconventional guerrilla counterinsurgency wars in Laos and throughout Indochina that were part of the regional war of resistance to decolonisation. The war, predicated on the fears of the Domino Theory, ended with none of the predicted outcomes. The foreign forces withdrew and the local nationalist-communist victors in Laos, Cambodia, and Việt Nam set about reconstruction with varying degrees of success and largely without assistance from the Anglosphere countries which had invested so heavily in the war. US forces left Thailand in 1975-76 at the request of Thai authorities. SEATO was disbanded in 1977. Australia’s forward defence doctrine was quietly forgotten.

Athol Townley, Australian Minister for Defence, 1958-63 (Airways Museum)

Athol Townley, Australian Minister for Defence, 1958-63 (Airways Museum)

[p. 2]

Introduction: the Problem

This thesis seeks to explain three aspects of Anglosphere participation in the US-led war in Laos between 1954 and 1975. It has been necessary to draw upon the far more extensive evidence from the Việt Nam theatre of the Second Indochina War. Some evidence for Laos was missing or not available at the time of writing. Much evidence was kept very secret at the time and has remained little known and rarely commented upon in the English-speaking mass media, popular or academic literature with a few exceptions. Both academic and popular histories have mainly ignored the roles played by the British and Commonwealth allies in Laos. An example of this incongruity could be observed on 7 February 2008, when then Australian Prime Minister, Kevin Rudd, was interviewed on the opening of a special wing at the Australian War Memorial (AWM) in Canberra for the Việt Nam War. The substantial A$17 million extension included no mention of Laos or the Australian troops who served in Thailand, which was the front-line for the launch of assaults on Laos. (2)

Secrecy, thought necessary at the time for military reasons, has hampered a thorough examination of the history. Few journalists ventured into Laos or Cambodia during the war. Wilfred Burchett was an exception and his Australian passport was confiscated. There were gaps in the archival record and restrictions remained on a number of documents that had not been assessed for declassification or remained firmly closed from public scrutiny. It is a problem for historians performing authentic research. British, Australian and New Zealand governments denied this collaboration at the time. Britain still denied involvement at the time of writing. Yet, the collaboration of these allies was extensive and significant, as this thesis will demonstrate.

The foundation for collaboration arose from interests in common with the South East Asia Treaty Organisation (SEATO) headquartered in Bangkok, which under-pinned the organisation of US allies and partners for the task at hand. (3) Members of SEATO also included a reluctant France, and Asian nations, Thailand, The Philippines and Pakistan.

[p. 3]

SEATO was a creature of the Cold War and a harbinger of constrained lives, with diminished civil liberties and undemocratic governance throughout South East Asia. Even with Asian member states, SEATO was an instrument of resistance to decolonisation. SEATO researchers distilled world news into interpretations of Communist threats in their “Trends and Highlights” reports. (4) In the US and to some degree in allied nations, communism was treated as a major threat to national security. Communism was regarded as a pathological contagion that would seep into any unguarded crevice. It could not be tolerated in any form or in the slightest degree. This is embedded in the language of counterinsurgency warfare. The anti-communist mindset, propelled by US Senator Joe McCarty’s Hearings on “Un-American Activities”, curtailed many careers, lives, families and friendships. Vern Countryman carried out an academic study, documenting how the Hearings proceeded. (5)

During Britain’s Cold War era, government agencies organised and censored what was made public through the Cultural Relations Department (CRD) and networks of compliant journalists and academics, as Richard Aldrich and others have explained. (6) Moyra Grant described the chilling effect on public discourse, in academia, politics and the media, as part of the architecture of censorship, caused in part by D Notices in Britain. (7) Christopher Simpson detailed how “Worldview Warfare”, as he termed it, which resulted in the stifling of dissident thought, common in a number of World War II and Cold War societies, and which could be weaponised for both ‘enemies’ and domestic populations. (8) In German, the word is Weltanschauungskrieg – a war of ideologies. It was used by the Nazis.

In this climate, the information dispensed by commanders to the lower ranks in the armed forces was made confusing and misleading for some, and for others simply not plausible. Fear of breaching the Official Secrets Act successfully kept many veterans from speaking out, as Australian RAAF veteran, Marc (also known as Mike) Holt demonstrated in his account of his service in Ubon, Thailand. In Holt’s own words, “…the Royal Australian Air Force ghost warriors who fought a secret war in Thailand to support the troops in Viet Nam

[p. 4]

have had to be silent for 40 years… more than 2,400 personnel served there between May 1962 and August 1968.” (9)

As the internet developed during the 1990s, veterans’ web discussions and web sites helped to reconstruct the narratives of their service in Thailand at Leong Nok Tha airfield, (Operation Crown) and on the road network, (Post Crown Works) till sufficient documents were declassified and made public. In some ways these forums were informative and supportive, but in other ways they also perpetuated confusion. Soldiers had been told that they were assisting Thailand with development of the impoverished North East and enabling agricultural products to be flown to Bangkok. They were in reality preparing for an invasion of Laos. This story was exactly what British Secretary for Defence, Denis Healey told the Parliament. As late as 12 April 1967, Healey maintained the fiction, in a House of Commons Question Time reply to Dr David Kerr, Labour MP for Wandsworth Central, that, “There is no connection between the work which we are carrying out to help the Thai Government to open up its country to Government services to enable local people to export their produce, and the events in Vietnam.” (10)

This secret war in Laos was not the first or only covert war which was promulgated by an intelligence agency rather than mainstream US military forces. Rather, it was one in a long list of CIA-commanded wars. Thus, officers and their paramilitary advisers and mercenaries were sent from one posting to another to carry out similar work. North Americans far from home required regular and reliable logistic support to enable their work. Deniability was an important feature of secret wars, and so the CIA chose to use the services of several privately-operated airlines. These were Air America and Continental Air Services. They fed up to 30,000 Hmong family members and fighters, resupplied weapons and the infiltration and exfiltration of CIA officers, making Long Tieng, Lima Site 20a one of the world’s busiest airports:

CIA/Air America plane and personnel (Background: Wikipedia)

CIA/Air America plane and personnel (Background: Wikipedia)

Air America was a CIA-owned and -operated “air proprietary” during the Cold War against the global menace of communism. From 1946 to 1976, Civil Air Transport (CAT) and Air America served alongside U.S. and allied intelligence agents and military personnel in the Far East, often in dangerous combat and combat support roles.

[p. 5]

Behind a shroud of strict secrecy, many Air America personnel were unaware that they were “shadow people” in counterinsurgency operations. Some 87 of them were killed in action in China, Korea, Laos, Vietnam, Cambodia and elsewhere. (11)

The Agency’s prominent officers, their roles and postings, have been detailed by John Prados. (12) Félix Ismael Rodríguez Mendigutia, veteran of the Bay of Pigs, ordered the execution of Ernesto “Che” Guevara, and was later posted to Việt Nam to join the leadership of the Phoenix Program, as he narrated on camera. (13) Secret irregular wars are fought covertly, by stealth, often in remote locations, deploying special forces, mercenaries and local proxies.

These wars usually begin on a small scale and avoid unwanted media attention. The list of operations compiled by William Blum was long, but may have some minor omissions. (14) The aborted Bay of Pigs (Playa Girón) covert invasion of Cuba of 17 April 1961, was a setback for US planners and their allies in Laos. (15) The Indochina War, especially in Laos, was initially a small covert war, but also developed into a big conventional war, with long-term planning, procurement, recruitment and training. John Prados described the CIA’s war led by its then Director, William Colby: “Shackley saw Lair’s rubber band and baling wire operation [in Laos] as a village market, but he wanted to run a supermarket, a high-intensity covert war.” (16) (CIA paramilitary case officer, James William (Bill) Lair, who directed the secret war from a building in the RTAF base, Udorn Thani). Prados has provided some definitions:

…the Joint Chiefs of Staff define a “covert operation” as one planned or conducted so as to conceal the identity of the sponsor or permit a denial of involvement… the U.S. military adds the “clandestine operation”, defined as one which emphasis “is placed on concealment of the operation rather than on the identity of the sponsor”…

He also commented on the success-rate of these operations,

[p. 6]

… American undercover actions have resulted in upheavals and untold suffering in many nations while contributing little to Washington’s quest for democracy. Despite considerable ingenuity… the results of covert operations have been consistently disappointing. (17)

CIA’s own legal Counsel, Lawrence (Larry) Houston wrote an ‘in-house’ opinion on 15 January 1962, that legality was an elastic concept to the CIA:

… there is no statutory authorization to any agency for the conduct of such activities. No explicit prohibition existed either … related to intelligence within a broad interpretation of the National Security Act of 1947. (18)

On some occasions the CIA and Britain’s MI6 agreed to collaborate. One of these was the coup d’état to overthrow the elected Prime Minister of Iran, Mohammad Mossadegh, in 1953. (19) Another example, in 1953, was the agitation in then British Guiana to prevent the election of trade unionist, Cheddi Jagan as Prime Minister. (20) These events and others ran concurrently with the early stages of the war in Laos. Documents show that Britain had taken a close interest in Laos, but it was most probably a CIA-led operation.

The CIA made assessments in 1961 that Laos was an insignificant country whose sovereignty need not be respected, as shown in one of its long-over-classified ‘Family Jewels’ documents released in 2008. Laos was described as “a diminutive jungle kingdom”. Yet, the document also states: “Laos is a peaceful country and the Lao people are dedicated to peace; yet Laos for more than twenty years has known neither peace nor security. Thus did the Laotian King Savang Vathana (Sic.) [Sisavang Vatthana] describe the anomaly that is Laos today.” This US Defense Department document was marked “SPECIAL HANDLING REQUIRED Not Releasable to Foreign Nationals 12 Of 15 TOP SECRET, EXCLUDED FROM AUTOMATIC REGRADING DOD DIP 5200.10 does not apply.” (21)

[p. 7]

This could help explain why Geneva conferences and agreements, with or without Britain’s ostensible perseverance in bringing about the withdrawal of foreign forces in Laos or ending the fighting, as described by Nicholas Tarling, had no prospect of success. Britain had very little influence with the US when decisions had already been made in Washington. As Tarling spelt out, “…it throws light on Britain’s policy in Southeast Asia in what, in some sense, may be seen as the last of the decades in which it was crucial… [the British government’s] essential task was to find ways of diminishing Britain’s role in a responsible way.” (22)

Both the North Vietnamese and the US had no intention of making the agreement and making Lao neutrality a workable arrangement that would bring an end to the fighting and bring peace, as Peter Busch concluded. (23) Britain and Canada used their presence on the International Control Commission (ICC) to transmit complaints about the North Vietnamese, whist minimising complaints against the US. (24) There had not been much change in US intentions from the time of the 1954 Geneva Conference and the determination of John Foster Dulles, US Secretary of State for President Dwight D. Eisenhower. (25)

John Foster Dulles, US Secretary of State, 1953-59 (Wikipedia)

John Foster Dulles, US Secretary of State, 1953-59 (Wikipedia)

Notes

2 “New Australian War Memorial Wings Opened by PM,” in AM (Australia: ABC Radio National, 2008). https://www.abc.net.au/am/content/2008/s2173642.htm (accessed 13 April 2010)

3 A fuller history of SEATO is provided on pages 24-28 of this thesis.

4 “South-East Asia Treaty Organization – Trends and Highlights,” Research Office (Bangkok: SEATO, 1965 ), (1 December 1965) B1, C4, C1, (16 January 66) C3, C5, (1 February 66) B4.

5 Vern Countryman, Un-American Activities in the State of Washington: The Work of the Canwell Committee (New York: Cornell University Press, 1951), 1-12.

6 Richard Aldrich, “Putting Culture into the Cold War: The Cultural Relations Department (CRD) and British Covert Information Warfare ” Intelligence and National Security 18, no. 2 (2003). 109-134

7 Moyra Grant, “The D Notice,” Serendipity, https://www.serendipity.li/cda/dnot.html (Date accessed: 5 January 2006)

8 Christopher Simpson, Science of Coercion: Communication Research and Psychological Warfare, 1945-1960 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994), 15-30.

9 Marc Holt, “Australia’s Secret Vietnam War Warriors?,” Big Chilli magazine, , https://searchwarp.com/swa77414.htm (Date accessed: 24 September 2008)

10 Britain, Debate, House of Commons, Ministry of Defence, “Thailand (British Army Detachment),” HC Deb 15 December 1967, Vol 744, 1175-61175.

11 Adrian Rosales Steve Maxner, “About Air America,” AirAmerica.org, https://www.air-america.org/index.php/en/about-air-america/aboutmenuaa.

12 John Prados, Safe for Democracy the Secret Wars of the CIA (Chicago, Ill: Ivan R Dee, 2006), xvii-xxix.

13 Felix Rodriguez, “Secret CIA Operations: Felix Rodriguez, the Bay of Pigs, the Death of Che Guevara & Vietnam ” (US: Youtube, 2014). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wjXUPbXczKQ (Date Accessed: 28 June 2015)

14 William Blum, Killing Hope: US Military and CIA Interventions since World War II, Updated edition ed. (Monroe, ME: Common Courage Press, 2004 ), Contents 4-5.

15 Prados, Safe for Democracy the Secret Wars of the CIA, 3, 10, 221,45,48, 59, 63.

16 Lost Crusader: The Secret Wars of CIA Director William Colby (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003), 167.

17 Safe for Democracy the Secret Wars of the CIA, xiv, xv.

18 Ibid., 291.

19 Ibid., 97, 98, 122, 23.

20 Ibid., 3, 13, 18, 19.

21 Directorate for Freedom of Information and Security Review US Department of Defense, “Chronological Summary of Significant Events Concerning the Laotian Crisis, First Installment: 9 August 1960 to 31 January 1961 (Revised Version),” Defense (Washington DC: US government, 1961), 1. https://www.vietnam.ttu.edu/star/images/250/2500113001A.pdf (Date Accessed: 20 December 2015)

22 Nicholas Tarling, Britain and the Neutralisation of Laos (Singapore: Singapore University Press 2011), 1-3.

23 Peter Busch, All the Way with JFK? Britain, the Us and the Vietnam War (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003), 54-57.

24 Ibid., 37-65.

25 John Foster Dulles, “Indochina – Views of the United States on the Eve of the Geneva Conference: Address by the Secretary of State, March 29, 1954 ” Avalon Law Project, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/inch019.asp (Date Accessed: 17 August 2010).

…

[p. 12]

Summary

Chapter 1 explains the building of military infrastructure in Thailand by Britain, Australia and New Zealand, SEATO’s essentially anti-democratic inclinations, the massive SEATO exercises, the plans for 28 Commonwealth Brigade Group to participate in a US-led invasion Laos from Thailand (which did not eventually proceed) and the inclusion of nuclear weapons in the choice of methods. Australia’s nuclear ambitions were also clarified.

Chapter 2 plots the careers of the counterinsurgency experts from Britain and Australia. Little corroborating material could be discovered regarding the activities of Myles ‘Woozle’ Osborn beyond his obituary. It is known that Osborn worked in Laos purportedly for the Royalist government, answered to MI6, directly with CIA counterparts, on recruitment of hill tribes, as Stephen Dorril explained. (51) The British Advisory Mission (BRIAM) the Strategic Hamlets programme and The Australian Army Training Team Vietnam (AATTV) led inexorably to Sir Robert Thompson and Colonel Ted Serong working for the CIA in the Phoenix Program that caused the assassination of between 20,000 and 30,000 South Vietnamese.

Chapter 3 follows the development of Agent Orange and other defoliants from Porton Down in Britain to its use in Indochina for both clearing jungle canopy cover and destroying food crops. It explains the toxicity and teratogenicity of dioxin, why it caused malformed infants, why it harmed allied combatants and how it was eventually removed from Việt Nam and destroyed. Defoliants were also manufactured in Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand for sale to the US. Australian veterans were treated with disdain when they made claims that defoliants had affected their health and that of their offspring.

Note

(51) S Dorril, MI6: Fifty Years of Special Operations (London: Fourth Estate), 712.

Sorry to hear that Willy Bach had passed away.

Reference Mr. Bach’s theory that the Leong Nok Tha airfield constructed by the British Army’s Royal Engineers between 1963-68 was constructed for use as a launchpad for operations against Laos insurgents by Commonwealth Forces bordered on the ridiculous.

I served with the Royal Engineers on Operation Crown and the road project Post-Crown Force for some 22 months and find Mr. Bach’s hypothesis riddled with inconsistencies.

I corresponded with Mr. Bach some 15 years ago disputing much of his synopsis on alleged clandestine military activities and to this day there is no definitive proof supporting his theory.

Mick Norton BEM