‘At war with the Braithwaites’, Honest History, 23 November 2016

Peter Stanley reviews Richard Wallace Braithwaite, Fighting Monsters: An Intimate History of the Sandakan Tragedy

Around the end of the 1960s the twenty-year-old Richard Braithwaite, then a university student, wore his hair long, as was the fashion. His hair annoyed his father intensely, a scene repeated in millions of families as generations clashed at a time of dramatic social change across the western world. But, reflecting on his father’s scorn nearly fifty years on, Richard Braithwaite realised that his father’s feelings derived from a particular experience, because Richard’s father (also called Dick Braithwaite) had been a prisoner of the Japanese twenty-odd years before. In January 1945, in the notorious prison camp at Sandakan, in North Borneo (later Sabah), the Japanese had impounded scissors, razors and knives. The prisoners’ hair and beards grew long and straggly. Only six of them (out of over 2500) survived to be liberated – the rest were killed or died of over-work, illness, starvation, most in the notorious Sandakan death marches, the last prisoners dying within days of Japan’s surrender. Richard Braithwaite later acknowledged the roots of his father’s disgust, explaining that ‘to my father, long hair and beards must have symbolised the ultimate loss of dignity and freedom, exactly the opposite of the freedom it represented to young people in the 1960s’. That insight into both the ordeal of Sandakan and what its history means is representative of this powerful book.

Around the end of the 1960s the twenty-year-old Richard Braithwaite, then a university student, wore his hair long, as was the fashion. His hair annoyed his father intensely, a scene repeated in millions of families as generations clashed at a time of dramatic social change across the western world. But, reflecting on his father’s scorn nearly fifty years on, Richard Braithwaite realised that his father’s feelings derived from a particular experience, because Richard’s father (also called Dick Braithwaite) had been a prisoner of the Japanese twenty-odd years before. In January 1945, in the notorious prison camp at Sandakan, in North Borneo (later Sabah), the Japanese had impounded scissors, razors and knives. The prisoners’ hair and beards grew long and straggly. Only six of them (out of over 2500) survived to be liberated – the rest were killed or died of over-work, illness, starvation, most in the notorious Sandakan death marches, the last prisoners dying within days of Japan’s surrender. Richard Braithwaite later acknowledged the roots of his father’s disgust, explaining that ‘to my father, long hair and beards must have symbolised the ultimate loss of dignity and freedom, exactly the opposite of the freedom it represented to young people in the 1960s’. That insight into both the ordeal of Sandakan and what its history means is representative of this powerful book.

Growing up as the son of one of the survivors of the death marches, Richard Braithwaite lived all his life in the shadow of that shocking event, the greatest single wartime tragedy in Australia’s Second World War. In Fighting Monsters, published and launched just days before Richard’s death from cancer in October, he weaves his family’s story into a re-telling of and reflection on the prisoners’ ordeal, the origins, cause and course of the death marches and the way the episode has been understood, interpreted and remembered. It is a complex story, one that takes its time, but so thoughtful, well-structured and expressed is it that it never drags. Having researched the story for decades – having looked into the abyss, as he quotes Nietzsche, fighting the monsters of memory of what he describes as a tragedy (and, remarkably, not so much as an atrocity) – Richard Braithwaite’s book deserves thoughtful consideration.

Richard Braithwaite takes his time to work through not just the events of 1942-45, culminating in the death marches and the escapes of a handful of desperate men, including his father, but also the prolonged aftermath for victims, Japanese, Australian and Sabahan. The six survivors all experienced degrees of trauma for the rest of their lives. Dick Braithwaite senior seems to have come off better than his fellows – the family of Bill Moxham endured years of violence, while Richard described Keith Botterill as a man who ‘had a face that vividly showed his torment’, and for decades, haunted by the memories he could not escape. (I met Keith when he contributed to the Australian War Memorial’s 1945: War & Peace exhibition in 1995, and endorse Richard’s judgment.) It is Richard’s detailed, thoughtful and well-informed insider’s account of Sandakan’s aftermath and how it has been interpreted, understood and remembered that makes Fighting Monsters among the most valuable of the many books on Sandakan that have appeared over the past sixty-odd years.

Of particular interest to proponents of Honest History is Richard Braithwaite’s attitude to his self-imposed task. He became a zoologist and academic, and professes that his training as a scientist gave him an ability to not simply accept long-standing explanations and interpretations, but to question them; which he does, following the evidence and logic where it leads rather than where he would like it to lead. Whether or not a scientific training enabled him to approach the events and the evidence in a more ‘objective’ spirit, the fact is that Richard refused to simply accept simplistic explanations, that the perversion of Bushido enabled Japanese soldiers to blindly follow orders that resulted in individual beatings and torture and, ultimately, mass killing or that ‘the Japanese’ were simply ‘evil’.

Unusually, Richard Braithwaite read his way into the problem not just by devouring everything he could find about Sandakan (including getting to know Sabah and its people). He also read the literature on the Nazi Holocaust, and the comparison led him to novel and fruitful conclusions. He bravely presents the prisoners as individuals who responded variably to the crisis they faced. Some responded selfishly, he acknowledges, including those who collaborated to try save their lives; others responded selflessly. The moral distinction pervaded Dick Braithwaite’s life thereafter: life divided people into givers and takers, a moral distinction that he often made. Richard Braithwaite’s analysis of his father’s various accounts of how he killed a Japanese straggler while escaping is, paradoxically, both carefully dispassionate and lovingly compassionate at the same time. This intimate association with the story and its protagonists on all sides gives Fighting Monsters its compelling tone.

Grave near track, 1946 (AWM 042578)

Grave near track, 1946 (AWM 042578)

One vital difference between this Sandakan book and just about all of the others (with the exception of Tanaka Yuki’s Hidden Horrors) is that Richard Braithwaite took the time to get to know the tragedy’s Japanese protagonists (who included its victims) and incorporates them into his story with a remarkable even-handedness. He had translated and published the memoir of Ueno Itsuyoshi, a soldier who suffered nearly as much as the unfortunate prisoners – he presents both as ‘pawns in this game of empires’. Richard Braithwaite’s father spent decades refusing to buy anything Japanese or to stock anything made in Japan in the business he owned in the 1950s. Remarkably, in time, that animosity softened and, thirty years after the war’s end Dick bought a Nissan Bluebird. His son, though, saw Sandakan’s effects on Dick – his flashbacks, characteristic of post-traumatic stress disorder, were obvious and visible, staying with him until he died in 1986. Because Richard Braithwaite refuses to simply take refuge in a frankly racist explanation for the tragedy, his deeply reflective and emotionally rich book demonstrates the value of an approach rooted in an open interrogation of the evidence.

Some accounts of Sandakan fail to pay sufficient attention to the setting of the tragedy, North Borneo and its people – Malay, Chinese and Indigenous. Richard Braithwaite came to understand the relationship between the people of Sabah and the harsh Japanese occupation that made its people victims of war along with the prisoners. Dick Braithwaite worked and lobbied Australian authorities to acknowledge and reward those who had succoured the prisoners – Dick and the others survived only because local people risked their lives to get them to Allied forces. Dick welcomed to Queensland in the 1960s the Funk family, whose members had risked imprisonment and torture as part of Borneo’s resistance, and Richard had the satisfaction of finding the family of Loretto Padua, one of his father’s Sabahan rescuers. In time Richard visited Sabah often, speaking about and with the Sabahans and forging friendships with the families who helped his father and other prisoners. Richard writes of his embarrassment when Australian visitors to Sabah, imperfectly aware of the full facts, appropriated the Sandakan story, ignoring or diminishing its Sabahan dimension.

Another distinctive aspect of Fighting Monsters is that, braided into the story Richard Braithwaite tells is the experience of his mother, Joyce; this is, as the title makes clear, an ‘intimate history’. As Joy, she had married Wal Blatch, who weeks before the outbreak of the Pacific war arrived as a reinforcement in the 2/15th Field Regiment, where he was assigned to Dick Braithwaite’s gun detachment. Wal and Dick went into captivity together and to Sandakan, where they laboured together on the airstrip as slave workers. The two became great friends, though Dick left Wal behind when he slipped away from certain death. At the war’s end Joy learned that Wal would not return, and in her grief decided she would no longer be Joy, but Joyce. Dick Braithwaite visited Joyce to tell her about Wal’s ordeal, and the two soon married. (Dick surmises that Dick was already half in love with her from Wal’s descriptions, but they acknowledged Wal’s part in their lives – Richard’s middle name is Wallace.) Joyce became as much a victim of Sandakan as her husbands, enduring Dick’s reactions (nightmares, of course, but also a withdrawal from social life and increasingly severe physical ailments). Joyce emerges as an admirable character in her own right, who, in her old age, well after Dick’s death, decided that she would no longer be defined as a widow of Sandakan and declined to speak about it publicly.

Fighting Monsters, though long, is worth sticking with. It is a work of wisdom in that Richard Braithwaite’s reflections on the entire episode bring him to comment on Australians’ relationship with the Pacific war, with Japan and the Japanese, and with the people of Sabah, whose beautiful land became the setting of so much suffering. He quotes the respected Australian Holocaust historian, Inga Clendinnen (who sadly herself died a month before Richard), that ‘it is better to be hurt by the truth than comforted by lies’, an aphorism apt for those urging the practice of Honest History. Richard Braithwaite offers a manifesto for thinking about the Pacific war, with its persistent self-righteousness and claims on both sides to victimhood. ‘Lose the hatred’, he urges, recognise how all those involved suffered, understand why Japanese soldiers behaved as they did, ‘seek a common history of the Pacific War’, ‘acknowledge the injustice of the war crimes trials’ and apologise to each other and seek ways of mutual healing.

It is a truism much repeated that the world wars scarred Australia and its people deeply. In general, the claim is usually and actually exaggerated, by seizing on terrible episodes (The Nek, Fromelles, the Montevideo Maru, Sandakan, for example) but then generalising and extrapolating unduly. Many families were of course touched by war, but only a minority were affected on the scale of the Moxhams, Botterills or the Braithwaites. The force of war’s impact on these few should not be under-estimated, and the awful stories of Sandakan’s victims, in 1945 and after, bear out the enduring power of war for those on whom fate frowns. The Sandakan story has been told many times, and deserves to be. It is fitting that it should be told again, and by a man who brought to the task a life-long knowledge and consuming interest in the event and its effects, and in a manner that illuminates and deepens our understanding. My only regret is that Richard Braithwaite died before he could read the responses that his labour so richly deserves.

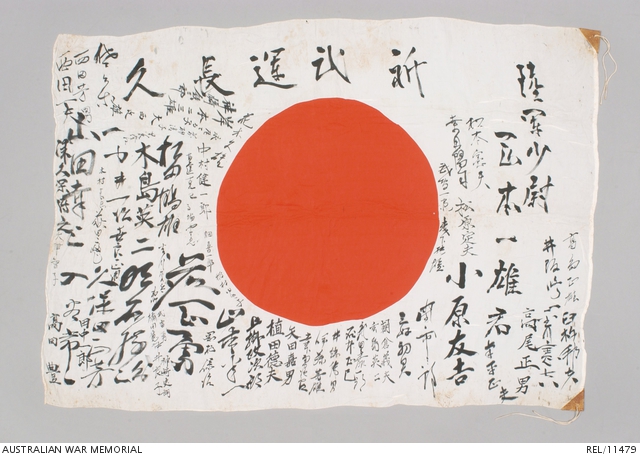

Autographed ‘good luck’ flag carried by 2nd Lieutenant Okamoto Kazuo, Sandakan (AWM REL/11479)

Autographed ‘good luck’ flag carried by 2nd Lieutenant Okamoto Kazuo, Sandakan (AWM REL/11479)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.