‘Anzac Day then and now – and probably for the future’ (review of Frame anthology), Honest History, 26 April 2016

Paddy Gourley reviews Anzac Day: Then & Now, edited by Tom Frame.

This book has been produced by the Australian Centre for the Study of Armed Conflict (ACSACS), a UNSW Canberra Research Centre at the Australian Defence Force Academy. It is a collection of essays focussing, says its editor, ‘on Anzac Day rather than on what are variously referred to as Anzac myths, legends and traditions’, although these, too, get a reasonable run. Most of the papers were delivered at a conference last year at ACSACS.

The contributors, Tom Frame, Jeffrey Grey, Carolyn Holbrook, Ken Inglis, Peter Stanley and others, all have significant standing in the field of military history broadly defined or, more accurately, ‘war history’. With opening and closing essays from the editor, the book is divided into sections dealing with the foundations of Anzac Day, the main features of its evolving commemoration, fractures in criticisms of Anzac observance, and the literary, religious and political ‘fervour’ that has sustained the commemoration.

The contributors, Tom Frame, Jeffrey Grey, Carolyn Holbrook, Ken Inglis, Peter Stanley and others, all have significant standing in the field of military history broadly defined or, more accurately, ‘war history’. With opening and closing essays from the editor, the book is divided into sections dealing with the foundations of Anzac Day, the main features of its evolving commemoration, fractures in criticisms of Anzac observance, and the literary, religious and political ‘fervour’ that has sustained the commemoration.

Anzac was bound to attract controversy and it continues to do so. The Gallipoli campaign was a military failure for Britain and its allies and it was part of a war about which the Australian historian Christopher Clark has said that ‘none of the prizes for which the politicians of 1914 contended was worth the cataclysm that followed’. The war’s protagonists, he goes on, ‘were sleepwalkers, watchful but unseeing, haunted by dreams, yet blind to the reality of the horror they were about to unleash’. In 1918, the Austrian writer, Robert Musil, got close to the pits of despair when he wrote in his diary that ‘[t]he war can be reduced to the formula: you die for your ideals because it’s not worth living for them’.

For Australia, whose national interests may have been less engaged than some of the other parties, World War I was a disaster. While readers of Honest History will need no reminding about the raw statistics, they’re worth stating: from a population of five million, around 60 000 were killed and more than 150 000 injured or taken prisoner. In economic terms, from 1914 to 1920, real per capital GDP declined at an average rate of 2.7 per cent and by 1920 public debt had risen to around 130 per cent of GDP. In the ten years to 1930 annual average per capita GDP grew at the paltry rate of 1.3 per cent annually.

Finally, the 1914-18 war was, of course, the first in a line of murderous military and political conflicts that, on some scales, could give the twentieth century a strong claim to be the worst in recorded human history. In this context, there can be little wonder that Australians have had different views about how best to commemorate Anzac Day, the extremities of which are epitomised by Alf and Hughie in Alan Seymour’s early 1960s play The One Day of the Year. Especially for those with strong views about this play, whether or not they’ve seen or read it, Dr Frame’s book includes a perceptive essay on how it might be best approached.

More generally, this collection of essays makes useful and interesting contributions to a better understanding of Anzac Day in lots of different ways. Its contributors try to assess what they see as weaknesses and strengths in the historical record and tackle things like CEW Bean’s views about Australians as ‘natural soldiers’ and the place of Anzac Day in the country’s national identity, whatever that elusive notion might mean.

They also look at tensions between celebration and commemoration and the difficulties and compromises about religion in Anzac services. Of war memorials, Ken Inglis says that, after his great examination of them, ‘I found little or no more of Christianity in the monuments of Anzac than in the sentiments of [the poet C J] Dennis’.

The changing roles of sundry Anzac Day ‘custodians’ are discussed. These include the RSL, religious authorities and, in the last 25 years, governments and politicians who, for various reasons, some of them honourable, have been willing to back their interest with amounts of money that are large by the standards of the other countries we’re usually comfortable to compare ourselves with.

The place of literature and hymns is given a good working over. ‘Abide with me’ has apparently become the most popular Anzac Day hymn. It was written by the Rev Henry Lyte, ‘when he was dying of tuberculosis in 1847’ and it’s said he ‘did not have military commemoration in mind’.

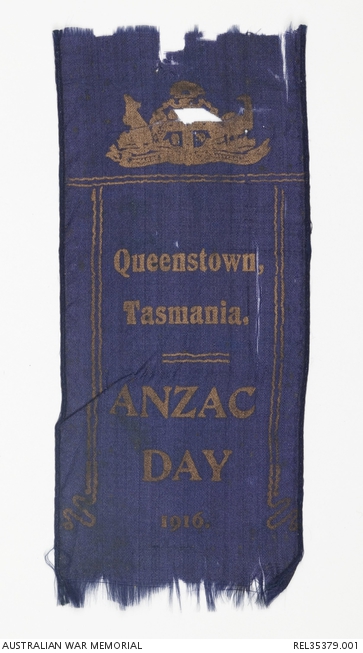

Silk bookmark, Anzac Day 1916 (AWM REL35379.001)

Silk bookmark, Anzac Day 1916 (AWM REL35379.001)

Professor Jeffrey Grey suggests that information about participation in Anzac Day ceremonies over the years is not easy to assess, although since 1990 there seems to have been a degree of waxing. Low cost air travel, among other things, has made it much easier for people to get to Turkey for 25 April each year and many seem to be keen to take advantage of this boon. Professor Frame says that while ‘it would seem that no-one has yet been able to identify the human need that is met by commemoration … it is difficult to imagine Anzac Day declining in the foreseeable future’.

Anzac Day: Then & Now is an elegant book. While a couple of its contributors may wear their learning a little heavily for some tastes, all the essays are clear, well-written and engaging, even when they are about relatively obscure aspects. Just one niggle: if, as ACSACS hopes, this book and others in its series are to ‘become standard reference works or textbooks’, it would be worth including indexes in future volumes, difficult as these are to do well. It’s a shame there’s not one in this one.

Anzac Day will always attract controversy and strong feelings. So if, as Professor Frame says, it will be around ‘for the foreseeable future’, this book deserves to be read by a wider audience than might normally be expected for a reference work or textbook. It has the potential to make many interested parties wiser and better informed.

* Paddy Gourley is a superannuated Commonwealth official who worked in the Department of Defence for ten years. He likes a good book and has previously done reviews for Honest History of books by Clive James (Last Readings) and Nathan Wise (Anzac Labour) and a collection edited by Bobbie Oliver and Sue Summers on remembrance in Western Australia.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.