‘Anzac and the militarisation of Australian society: Politics in the Pub, Glebe, 9 April 2015’, Honest History, 23 May 2015

(A video of the speech is on the Politics in the Pub website. Q&A. An associated speech.)

I acknowledge the Gadigal People of the Eora Nation, the traditional custodians of this land, and their elders past and present. My talk is in three parts:

- Anzac as it stands at present: during the centenary of Anzac; and I’ll be introducing a concept called ‘Anzackery’;

- the militarisation of our society: though I want to define ‘militarisation’ in a special way;

- one particular aspect: targeting of children.

Anzac

Anzac

First, Anzac. The bare facts:

- an invasion of the Ottoman Empire 100 years ago this month;

- the invaders cling on for eight months;

- 9000 Australians killed, 18 000 wounded.

The Australian part is a very small part of one big conflict: we were 5 per cent of the troops engaged (both sides) and 5 per cent of the casualties.

What happened next? All sorts of things were read into this event: the birth of a nation; doing our bit for the King and the Empire; washing away the convict stain.

There was commemoration almost from the beginning:

- the first memorial to the Dardanelles campaign was in Adelaide in September 1915;

- the first ‘official’ Anzac Day was in 1916.

Anzac commemoration waxed and waned over the next 100 years: see Carolyn Holbrook’s Anzac: the Unauthorised Biography). There were suggestions at times that Anzac Day would not survive; everyone knows about (the late) Alan Seymour’s play ‘The One Day of the Year’ (1960). But at the same time there seemed to be the growth of certain ‘Anzac values’ (mateship, resourcefulness, courage, etc.); they were really universal values but we tended to think they were particularly Australian.

Ken Inglis as early as 50 years ago suggested Anzac was a ‘secular religion’ or sometimes he said a ‘civic religion’. It’s not a bad analogy: Anzac as a religious denomination; it is not the established church; like any religion it is not compulsory; atheists and agnostics and people of faith mostly tolerate each other. The religious analogy is helpful

More recently, Christina Twomey has written about how Anzac – military commemoration – fits into a culture of trauma, where people identify with the suffering of people they’ve never met, where they empathise without ever really understanding – or bothering to understand – the historical events, large and small, that led to that suffering. Perhaps the communal grief over the death of the Princess of Wales twenty years ago was an early (non-military) example of this.

However, when looking at the rise of Anzac in the last 25 years, the template that I’ve found particularly useful is one which is essentially about narcissism: looking into a mirror for images larger than ourselves. The type of commemoration exercise we engage in nowadays is less about them – the Diggers – and more about us – about Australians today.

Michael McGirr, writing in 2004, noted how ‘the remembrance of war is moving from the personal to the public sphere’. He went on that quiet and dignified remembrance of others had become noisy – ‘an unrestrained endorsement of ourselves’ which devalued the forebears we claimed to revere. ‘People now seem to believe that in looking at the Anzacs they are looking at themselves. They aren’t. The dead deserve more respect than to be used to make ourselves feel larger.’

Mark McKenna, I think it was, wrote about some young backpackers, interviewed at Anzac, who were asked why they were there and the answer was, ‘it’s not about them [the Diggers]; it’s about us’.

That’s a good point to introduce you to the concept of ‘Anzackery’. Using that term ‘Anzackery’ is not meant as a gratuitous insult to Anzac Day; I personally have nothing against Anzac Day provided it’s done with dignity. Nor is it meant to insult those who do practice the secular religion of Anzac.

‘Anzackery’ is meant, instead to describe overblown, jingoistic, sentimental commemoration or celebration of Anzac – often with commercialisation thrown in. The term was coined by Geoffrey Serle nearly 50 years ago, when he recalled ‘fire-breathing generals’ coming to speak at his primary school in the 1930s on the theme of how Australia had been born at Gallipoli.

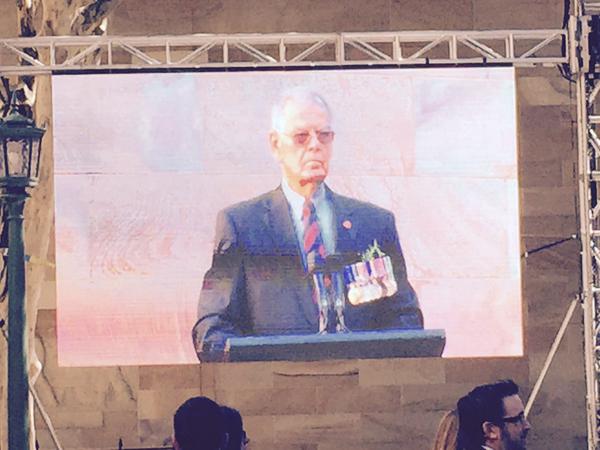

Colonel Arthur Burke (Windsor State School Twitter page)

Colonel Arthur Burke (Windsor State School Twitter page)

Here are two quick examples. The first is from Colonel Arthur Burke who is with the Anzac Day Commemoration Committee of Queensland

The Spirit of ANZAC is invincible. It is the flame that burns forevermore in the heart of every true Australian and New Zealander. Today we stand safe and free, clothed with all the privileges and rights of citizens in these great free countries. And all these things – liberty, security, opportunity, the privileges of citizenship – we owe to those men who fought, endured, suffered, and died for us and for their country. Their deeds and their sacrifices gave us the invincible, the intangible, the Spirit of ANZAC.

The second is from … actually, see if you can guess

One clue, it is a former prime minister

Our identity has been etched deeply by what we call ANZAC. For nearly a century … ANZAC has occupied a sacred place not far from the nation’s soul. It shapes deeply our nation’s memory. It shapes deeply how we see the world. A hundred years later, it shapes too what we do in the world. Neither religious nor secular, whatever our beliefs are, ANZAC is profoundly spiritual – inspiring pilgrimages still to that far-off place where our modern-day pilgrims drink deep from the well of national memory … I believe each generation of Australians has a duty to pass this torch to the next.

Guesses? Kevin Rudd 2010.

Militarisation

Let’s move on to the next part of my talk: militarisation. I want to refine the definition of the term ‘militarisation’. It doesn’t mean everyone going around in uniform. Also, militarisation doesn’t mean a massive conspiracy by the Department of Veterans’ Affairs to flood schools with books praising military things. (You will know about the book What’s Wrong with Anzac? from 2010, where this sort of argument is put; personally I think they overcook the argument a bit.) DVA does put out lots of books like that but a lot of them get put in the bin. Teachers are pretty good at working balance into their lessons.

DVA is an example, though, of top-down influence, official or governmental influence on the general populace. But there is also a lot of bottom-up influence, leading towards an upward curve in the interest in military things: the interest in family history; old Diggers dying off conspicuously; backpackers going to Gallipoli; TV shows on military subjects.

So when we get a lot of officially-sanctioned commemoration over the next few years, it will be eagerly lapped up. When we from Honest History, about 18 months ago, spoke to a senior government official involved in commemoration and asked what the official felt was driving the then impending splurge in commemoration, the answer was, ‘It’s what the bogans want’.

The official didn’t mean by ‘bogans’ the government that had just been elected – the previous government had made a flying start in Anzac centenary commemoration – but rather the voters, the people whose views were conveyed through focus groups and so on to the government and the official commemoration industry.

Having said all that, let’s redefine militarisation as it exists today. I want to call it ‘bellicosity’ or ‘belligerence’, if you like. It’s our increasing inclination to go to war – or to support government initiatives to send a limited number of people to war. As someone called it recently, our inclination to ‘take part in every war that’s going’.

Hugh White (ANU)

Hugh White (ANU)

Hugh White of the ANU looks at a number of reasons for this (for example, the importance we attach to the American alliance) but I want to pull out one in particular. White reckons that when governments start to rattle the sabre they appeal to a solid proportion of the Australian community who accept such action as a normal part of ‘who we are’.

White argues that this is partly due to ‘the potent idea of war in Australian society, focused on the Anzac legend’. He goes on that our ‘intense focus on military history, centred on the Gallipoli campaign, has shaped, and in some ways distorted, both our understanding of Australia’s history and our image of ourselves’. We have come to believe that ‘the experience of combat brings out personal qualities’ which are ‘essential to Australia’s national character’.

So militarisation is about a belligerent or a bellicose tendency – a tendency to think that fighting is important – but a tendency that some of us feel is essential to being Australian in the early 21st century. Militarisation is about the normalisation of bellicosity. It’s about making us think that a readiness to plunge into war is in our DNA, part of our genetic make-up. Which makes it important to look at the next generation.

Children

I want to talk now about the targeting of children. One thing you notice in the work we are doing at Honest History is how much commemoration – including Anzackery – is directed at children. Let me take you through a few examples. Michael Ronaldson, minister for the centenary of Anzac, often makes speeches about the ‘obligations’ on young Australians to carry forward the torch of remembrance. Angus Houston, when he was chair of the Anzac Centenary Advisory Board, said we needed to treat Anzac centenary with the ‘reverence it so deserves’ and ensure that ‘the baton of remembrance is passed on to this and future generations’. (He preferred the baton to the torch.) Kevin Rudd, in the speech I quoted earlier, talked about ‘duty’. Prime Minister Gillard more than once said it was great to see the number of children at Anzac Day services.

There is constantly this official focus on involving children. You see it also in official institutions. For example, in the final room of the refurbished World War I galleries at the Australian War Memorial, there is a large photograph – part of a montage – of a 1950s Australian grandfather and his grandson; the ‘passing the torch’ message is clear.

Then there is the War Memorial’s Commemorative Crosses project: the idea there is to plant a plywood cross for every one of 102 000 Australian war dead, either in their graves overseas or on memorials, where there is no known grave. On these crosses are messages penned by school-children – they are coached what to write – along the lines of ‘thank you for your sacrifice’ or ‘you died for our freedom’. The Memorial’s promotions include a picture of Director Nelson handing these crosses out to children, almost like communion wafers.

‘While in the Discovery Zone see if you would have made a good Iroquois pilot’ (Australian War Memorial)

‘While in the Discovery Zone see if you would have made a good Iroquois pilot’ (Australian War Memorial)

There are other educational programs at the Memorial; they are partly paid for by Lockheed Martin, the world’s largest arms company. There’s the Discovery Zone, where you can fly in an Iroquois helicopter from the Vietnam era, complete with battle sounds, or you can dodge a sniper – that’s how they advertise it on the Memorial’s website – in a simulated, but sanitised, World War I trench.

Then there are the books targeting children. On the Honest History website we recently reviewed a patriotic little production called Anzac Ted, about a teddy bear that keeps soldiers safe. That book, according to the author, is aimed at all ages from three upwards; if you are too young to read it, you can have it read to you by granddad, while you cuddle your Army teddy bear ($29.99 from the AWM shop) and snuggle into your camouflage pyjamas, also at the shop.

Then there is a book called Audacity, published by the Department of Veterans’ Affairs and the Memorial and aimed at 10-12 year olds. It’s about various war heroes. The theme is how being brave wins medals; in a book of about 50 pages there are 17 full colour pictures of sets of medals as well as classroom exercises about designing medals. So it’s linking the themes of being brave in war with doing good work at school.

Another classroom exercise in the booklet is based on a game that pilots in Bomber Command played in World War II, essentially the game was who could get closest to the bomb target and take a photograph. The instructions for this exercise are illustrated with an aerial photograph of the bombing of Hamburg in which there were 80 000 civilian casualties, including 42 000 deaths, more than the number of Australians killed in the whole of World War II. There is, of course, no mention of that for the kids; war books for kids are not good on context.

There are lots of other examples. Will this have a lasting effect on children? We don’t know how many schools use these booklets or how many parents buy camouflage pyjamas or Army teddy bears. Or how firmly the kids writing on the plywood crosses ‘connect’ with those dead Diggers (the objective as explained by the War Memorial people concerned).

Children deal with lots of myths and stories when they are young – the Easter Bunny, Virgin Birth, and so on; they sift them as they get older. Maybe Anzackery gets sifted out, also. But the pressure on the young is so great. We always say we don’t ‘glorify war’ but we sure do a lot of commemorating of it and there are always wide-eyed children in the front row, taking it all in. And there is evidence that the first impression lasts – a sanitised or a glorified view of war (an Anzac Ted view, for example) leaves an imprint on a child that affects the later information that is received about war.

Which takes us back to militarisation. Even eight or ten years ago, Anna Clark, a historian of the teaching of history, was surprised how many 15 year olds – girls as well as boys – thought that a ‘militarised national identity’ was an intrinsic part of being Australian.

I want to quote Minister Ronaldson again and I’ll quote this exactly because it relates to something I’ll say in a moment. He made another speech last year to Sydney Legacy, where he again talked about the responsibility of young Australians to carry forward the torch of remembrance.

Then he went on:

And when they [young Australians] hop on a school bus, or they walk home, or they go shopping, or they go out at night with relative freedom – that they realise in many instances that freedom has been paid for in blood. And they must understand that.

They ‘must understand’ that their freedom had been paid for in blood. Hold that thought.

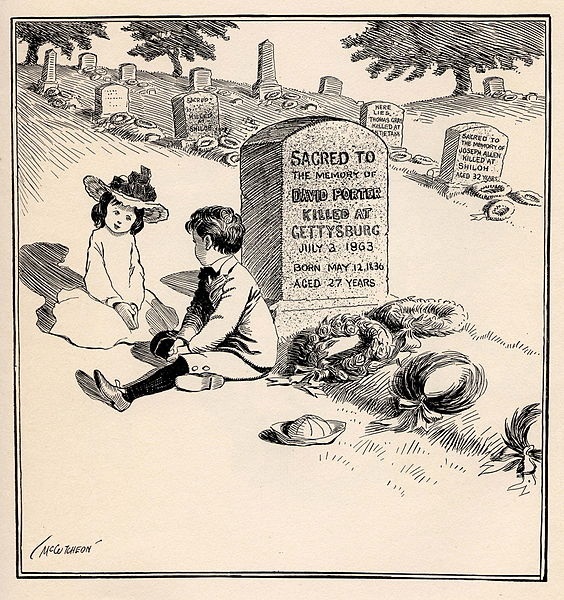

Decoration Day: ‘You bet I’m goin’ to be a soldier, too, like my Uncle David, when I grow up,’ c. 1900-05 (Wikimedia Commons/John T. McCutcheon)

Decoration Day: ‘You bet I’m goin’ to be a soldier, too, like my Uncle David, when I grow up,’ c. 1900-05 (Wikimedia Commons/John T. McCutcheon)

There’s a poem by Osbert Sitwell, called ‘The Next War’, written in 1919. The poem describes some plutocrats deciding what would be an appropriate war memorial and one of them says – and compare this with the remarks of Minister Ronaldson:

“What more fitting memorial for the fallen

Than that their children

Should fall for the same cause?”Rushing eagerly into the street,

The kindly old gentlemen cried

To the young:

“Will you sacrifice

Through your lethargy

What your fathers died to gain?

The world must be made safe for the young!”

And the children

Went . . .

Osbert Sitwell’s poem describes the implications of Michael Ronaldson’s speech. The minister’s implication is that freedom, ‘paid for in blood’, may have to be redeemed in similar fashion in the future.

Which goes back to my definition of militarisation – the building-in to the culture of a willingness to go to war. Normalising bellicosity. That’s our legacy to future generations: the expectation that honouring the war dead of the past – carrying the torch – requires the preparedness to become the war dead of the future.

This article contains the views of the author, not necessarily those of all supporters of Honest History.