‘Afghanistan: The Australian Story shows war is about much more than “love and friendship”’, Honest History, 2 May 2017

Serendipity can be illuminating. This reviewer began to watch Chris Masters’ double DVD, Afghanistan: The Australian Story, on the very day that Fairfax published a long article (based on government documents) on how Australia’s Iraq involvement was essentially a cynical downpayment on the American Alliance.

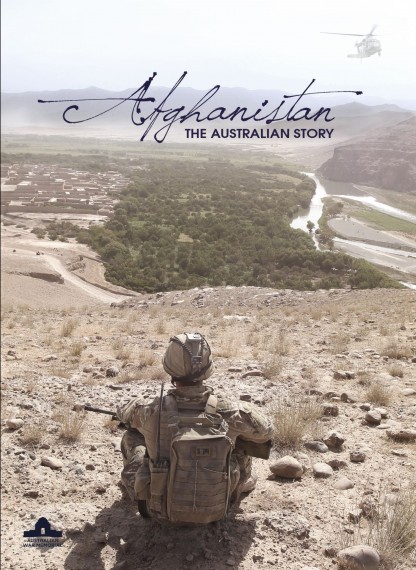

Masters made this documentary for the Australian War Memorial (with the co-operation particularly of curator Rebecca Britt) to coincide with some retooling of the Memorial’s galleries showing recent conflicts, including Afghanistan. (The Memorial’s main Afghanistan exhibition opened in August 2013.) There are two DVDs: the main program of an hour or so, plus an ‘extras’ compilation of 39 edited interviews, running to more than three hours. (This reviewer watched the main DVD twice and the extras once.)

Masters made this documentary for the Australian War Memorial (with the co-operation particularly of curator Rebecca Britt) to coincide with some retooling of the Memorial’s galleries showing recent conflicts, including Afghanistan. (The Memorial’s main Afghanistan exhibition opened in August 2013.) There are two DVDs: the main program of an hour or so, plus an ‘extras’ compilation of 39 edited interviews, running to more than three hours. (This reviewer watched the main DVD twice and the extras once.)

The most consistent theme in the whole package is how well Australians fight. As Henry Reynolds pointed out in Unnecessary Wars, this has been for more than a century a constant thread in Australian depictions of war and military life. Masters has previously expressed his admiration for the Australian soldier. (And again.) This package gives a bit more prominence to navy and air force as well as army personnel, but the emphasis on fighting – and fighting well and with zest – is obvious throughout, regardless of colour of uniform (‘game on’, ‘the way we fight is what I’m most proud of’, ‘not a peace-keeping mission but a real war’, ‘we couldn’t walk out of the patrol base without being shot at’, ‘there’s always the potential for danger’, ‘some of the fiercest fighting since the Vietnam War and a lot of it’). There is some graphic film of combat.

There is, secondly, a lot of pride in professionalism (‘it has to be 100 per cent’, ‘doing the job I’d been trained to do’, ‘the ultimate opportunity to test your skill set in the worst possible environment’, ‘everybody giving their best for six months’). These are highly trained, professional soldiers, sailors and airmen and women talking thoughtfully about what they do and taking pride in identifiable achievements. (There are some civilians, too.) The words are mostly carefully chosen and the language is modern: while these men and women are – according to politicians’ rhetoric and defence force tradition – ‘the descendants of the Anzacs’, their descriptions of war are very different to what would have come from the volunteer soldiers of a century and 75 years ago. They are skilled military technicians rather than instinctive Diggers.

Thirdly, there is empathy and compassion for the people of Afghanistan. One interviewee, Captain Daniel Fussell, describes how people in the fields paused only momentarily as the bullets flew over them: ‘nobody should be that used to war’. We see Australians providing medical and training assistance and talking to tribal leaders and their womenfolk. There are close-up depictions of medical help for children and women, as well as service people. The extent to which the people deployed to Afghanistan attempted community assistance and civil reconstruction is another clear difference from earlier generations of uniformed Australians.

There was also, we are told at one point, closer involvement with the people of Afghanistan than American forces often managed. Yet there is still something slightly patronising in the frequent Australian references to ‘the locals’. There is no denying also that mutual suspicion between coalition forces and the people is as common as mutual respect, even when the Afghans the Australians are dealing with are themselves soldiers (‘we never really trusted them completely’).

Alexander the Great invades Afghanistan, BC 330 (Wikimedia Commons/mosaic from c. BC 100)

Alexander the Great invades Afghanistan, BC 330 (Wikimedia Commons/mosaic from c. BC 100)

There is not much here about mateship, other than by implication, although Corporal Mark Donaldson VC has a telling sentence or two right at the end (significantly – it works well as a coda) about the bond of brotherhood – staying alive and keeping your buddies alive. There are plenty of references, though, to how service comrades become ‘family’, particularly because of the long absence from ‘real’ families. Bereaved real families become close to their dead husband or son’s former comrades.

Nor is there much about violent death. We hear Private Proficient Paul Warren talking about the death of Private Ben Ranaudo, Warrant Officer 2 Dan Costelloe about the death of Sergeant Brett Till, Captain Nick Perriman on the death of Private Andrew Jones in a green on blue incident (‘stay with me, Jonesy’), and Elvi Wood describing how she learned of the death of her husband Sergeant Brett Wood and her reaction to this event: she was sad but not bitter because he was doing what he loved and what he believed in, serving his country.

There are two notable long descriptions about injury, both told from two sides. Sergeant Troy Simmonds was surprised to be wounded but impressed nurse Wing Commander Sharon Bown by his politeness on regaining consciousness in the hospital (‘thank you, ma’am’). Lance Corporal Gary Wilson talks about the effects of his injuries, including brain damage, and his wife, Renee, describes his long recovery.

There is not much in the DVDs about why we were in Afghanistan. The DVDs’ blurb makes clear where the focus will be sharpest:

Australia’s mission was clear: to combat international terrorism, to help stabilise Afghanistan, and to support Australia’s international alliances. But a mission statement cannot reveal the challenges, the successes, and the comradeship of the Australian men and women who pursue it. Nor does it express the joys and heartbreaks, the loneliness and the dedication, of those who wait at home.

Private Brent Rothwell, Tarin Kowt, 2013 (Wikimedia Commons/SGT JA McCormick)

Private Brent Rothwell, Tarin Kowt, 2013 (Wikimedia Commons/SGT JA McCormick)

Masters’ early narration glides from counter-terrorism to counter-insurgency in a sentence and few of the interviews linger on the ‘why’ question. The general idea was to rebuild the country ‘one mud brick at a time’, says an interviewee, perhaps with a touch of irony. There is very little musing about the purpose of it all, about whether it was worth it, until right at the end of the main DVD. Here, Brigadier Jason Blain is level-headed, not overclaiming the degree of success. Brigadier Dan Fortune says ‘was it worth it is a really tough question’. Paul Warren (who lost a leg) ‘would go back tomorrow to finish that fight’. Medic Corporal Hollie McBride focuses on individual medical successes. Corporal Tim Raper reflects on the deaths of comrades and wonders if Afghanistan is better now than it was before. Chaplain Rob Sutherland sidesteps the key ‘worth it?’ question but notes the pride those who went will feel in a job well done.

Finally, on what happens next, there is proportionately more in the extras compilation than in the main DVD but about the despair that afterwards can lead to suicide there is hardly a word in the main DVD and not much more in the extras. Masters tells us in voice-over that all of these men and women returned ‘forever changed’ but the visuals at this point are discreet, and there is less interview material. This may be partly out of respect for privacy but one feels that an organisation like Soldier On could have provided evidence for this part of our Afghanistan story. Given the suicide toll of recent service personnel includes some who served in Afghanistan, the lack of reference to extreme personal responses to deployment is a glaring gap. On the other hand, there is ample material on the impact on families (wives are rocks and children gradually get used to fathers being away) and more on the wrench of leaving and the anticipation of coming home.

Masters’ work at the Memorial’s behest certainly gets beyond one of the Memorial’s sillier recent marketing taglines – that the Memorial, and commemoration generally, ‘is not about war. It is about love and friendship.’ That ‘either-or’ binary is simplistic, even crass. (Why do some of us so feel the need to reduce war’s jumbled elements to simplistic commemoration? Is it just marketing – simple stuff brings people through the doors – or is it fear of having to expose something that will turn people away?)

Masters gives us instead a layered and nuanced view of the Afghanistan adventure, certainly enough to reveal the complexity of war and of the experiences of those who fight it. Leaving aside the big gap about post-deployment suicide, one still looks for relatively less evidence of how a professional fighting force goes about its work and relatively more probing on the impacts post-deployment and on families. Was the lack of such material due to reticence by the interviewees, editing by Masters and his team, or editorial supervision by the Memorial?[1]

Australians, Tarin Kowt, 2013 (Wikimedia Commons/SGT JA McCormick)

Australians, Tarin Kowt, 2013 (Wikimedia Commons/SGT JA McCormick)

There are effectively three layers of evidence: the original raw interview footage (which, understandably, we don’t see); the edited interviews, five minutes or so each, often heavily edited, on the extras DVD; the shorter, even more heavily edited, snippets used in the main DVD. This editing leaves an uneasy feeling. Nowhere do we hear the questions which the interviewees answer. One cannot help but recall the story of the heavy editing that Charles Bean undertook to produce The Anzac Book, being fully aware of the book’s propaganda purpose. Is there an element of this in ‘The Afghanistan DVD’? Or were the subjects just given a general open-ended question, ‘Tell us about Afghanistan’, and away they went on a stream of consciousness?

Secondly, the people interviewed are disproportionately officers. Again, there is a Charles Bean precedent: his Official History of World War I has been seen as war from the officers’ perspective, since he mostly spoke to them. About half of Masters’ interviewees are at the rank of Lieutenant or equivalent and above, whereas the 26 000 or so total deployment to Afghanistan would have been about ten per cent officers. (Of the 41 ADF members killed, just three were officers.) This is surely not simply a question of articulateness: some of the ‘other ranks’ interviewed are remarkably fluent and thoughtful (Private Andrew Fox-Lane, Mark Donaldson, Tim Raper, Paul Warren, for example), whereas some of the officers have a corporate ADF-speak tone to their contributions (‘generation of superior tempo’, ‘aero-medical evacuation assets’, ‘better mission success’, ‘that changed the battle space’, ‘the risk proposition starts to change’) while showing a genuine concern for their men and women.

All in all, this is a reasonably balanced view of Afghanistan, given its auspices. The War Memorial is not renowned for asking fundamental questions about our wars and Masters was working for the Memorial. It is to be hoped that the full story of Australia’s Afghanistan involvement does not take as long to come out as did the redacted story of our Iraq involvement. When that full story does arrive it may be possible to make a proper judgement about whether the dedicated and skilled men and women interviewed by Masters made a difference to Afghanistan, as well as being part of the premium paid on the American ‘Alliance’.

A further, more important question remains: might this skill and commitment have been better employed in places where there could be a sharper focus on doing good as the main purpose of the involvement, not just as something jammed into the interstices of a brutal war (though played up for public relations purposes) while a wary eye is kept on ‘locals’ who want to do you harm – and who are more than likely to unpick much of your good work within a couple of years of you leaving (as reports about Uruzgan post-Australia and Afghanistan generally suggest)?

Wau refugee camp, South Sudan (Wikimedia Commons/J. Craig/VOA)

Wau refugee camp, South Sudan (Wikimedia Commons/J. Craig/VOA)

If Australians fight not to conquer but to serve, as Tony Abbott used to say, why not look for opportunities for our highly trained ADF to serve where they would not be directly involved in fighting, where they could focus on serving? This would mean being driven by human needs rather than by the imperatives of the Alliance or the need to work out regularly with ‘our American cousins’ or try out expensive military kit purchased from US companies. This year, 2017, may well see hundreds of thousands of refugee deaths in camps in Nigeria, Somalia, South Sudan, and Yemen. Those places could do with some help from highly trained army medics, skilled engineers, and good-hearted uniformed professionals generally.

Finally, there is left the question that hangs over all our wars – the same question that Henry Reynolds dealt with in Unnecessary Wars. Beyond the assurance that our boys and girls, in Rugby League coach Jack Gibson’s terms, ‘done good’, beyond the professional satisfaction (and promotion opportunities and on-the-job testing and training) obtained by servicemen and women, beyond the Alliance pay-offs, can we be sure that Australian governments properly weigh the costs in lives and psyches, Australian and non-Australian, before they get into adventures like Afghanistan and Iraq? There is nothing in these DVDs that helps answer that question. Worthy attributes like professionalism, dedication, patriotism, and yes, mateship, deserve not to be prostituted to unworthy causes.

Endnote

[1] Honest History would love to receive a response from the Memorial on this point and, as always, we undertake to reproduce the response without amendment. We do not hold out much hope that there will be such response, as contesting with constructive critics – or even responding to straightforward queries in a timely manner – is not the Memorial’s forté.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.