Derek Abbott[*]

‘Coming to grips with Grandpa, Japan and wars’, Honest History, 18 August 2018

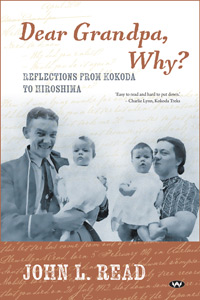

Derek Abbott reviews Dear Grandpa, Why? Reflections from Kokoda to Hiroshima by John L. Read

Edward Mobsby, ‘Mobs’ to his mates, enlisted in the RAAF in January 1941, was posted to New Guinea in 1942, then shot down and killed in July of that year, while flying as the co-pilot in a USAAF B-25 bomber. His aircraft had been damaged in earlier operations, the aircrew were tired and the superiority of the Japanese Zero fighters was such that the sortie, in the words of the squadron’s commanding officer, ‘closely approached being an all-out suicide mission’. The aircrew were all posthumously awarded the Silver Star, but Mobsby’s got lost in the inter-Allied bureaucracy and, after an extended effort by his daughters, was finally presented to them at a ceremony in Canberra in 2014.

Edward Mobsby’s story is deeply moving; it has elements that are all too familiar. The initial advice to his wife Joyce that he is missing in action; the long delay until confirmation of his death; the struggle to discover details of what has happened and to recover personal belongings; children deprived of a father. There is some small consolation that the persistence of his wife, daughters and other family members was eventually rewarded, that Mobsby’s story is now properly recorded, and that his family have received his medal.

Edward Mobsby’s story is deeply moving; it has elements that are all too familiar. The initial advice to his wife Joyce that he is missing in action; the long delay until confirmation of his death; the struggle to discover details of what has happened and to recover personal belongings; children deprived of a father. There is some small consolation that the persistence of his wife, daughters and other family members was eventually rewarded, that Mobsby’s story is now properly recorded, and that his family have received his medal.

This book, by Edward Mobsby’s grandson John Read, is about much more than a grandfather’s story. Indeed, it is much more about the author than his grandfather. Despite as a young man accompanying his mother to visit her father’s grave in the Bomana Cemetery outside Port Moresby, Read seems to have had little interest in his grandfather until, in mid-life with a young family of his own, and at the centenary of Mobsby’s birth, he became ‘intrigued … a little lost and sad but mostly confused’.

The author is puzzled as to why ‘a 30-year-old, with young twins he adored would sign up to fight a war in another country’. In seeking to answer this question, Read raises a multitude of others – strings of questions are a characteristic of his style – some definitely worth asking, others more rhetorical and some unanswerable: no amount of white water rafting or bungee jumping will replicate the experience of Mobsby and his crew; I don’t think drawing parallels with joining the French Foreign Legion or a gap year backpacking help to illuminate the motivation of young men enlisting in World War II.

Read, by his own admission no great reader – one book is described as a ‘boffiny tome that I struggled to read’ – and with no particular prior interest in the historical period, embarks on a course of ‘self-education’ in the history of the war, particularly in the Pacific. Phrases such as ‘I was hoping for some easy answers’, ‘I had naively assumed’, and ‘it turns out … that the situation was far more complicated’ recur throughout. Some of Read’s commentary may strike the reader as a bit naïve, as he discovers that his assumptions about the causes of the war were more than a little simplistic.

The book has a number of potted histories drawn from the author’s reading and it is clear that he has made a determined effort to move beyond the ‘goodies and baddies’ history he learned at school or picked up along the way. Thus British and European colonialism, its impact on Asia, and its influence on Japanese attitudes to their need for resources, are all covered, but the brevity of these sections tends to raise almost as many questions as they answer.

The last third of the book is taken up with Read’s contact with a Japanese family whose father was a fighter pilot in New Guinea at the same time as Edward Mobsby and may have been involved in the engagement in which Mobsby was shot down and killed. This contact leads the author to visit Japan, spend some time with the pilot’s family and, inevitably, ask many questions about how modern Japanese view the war and their responsibility for it. He is at first surprised that there is an alternative view of the causes and conduct of the war, the motivation for US sanctions prior to the war, the ‘morality’ of the attack on Pearl Harbor, the conduct of Japanese forces, and the use of nuclear bombs.

Read’s book becomes a wide-ranging speculation not just on what motivated his grandfather and others like him to enlist but also on the history of World War II, and thence on the causes of war generally and how armed conflict can be avoided today. As a professional ecologist, Read has a very clear appreciation of the potential for conflict arising from population pressures, the impact of climate change and competition over water, food and other resources. He is deeply and properly concerned that the world could blunder into a major conflict and quotes former Secretary of the Departments of Defence and Foreign Affairs and Trade, Dennis Richardson, in support of his contention that Australia puts too little effort (and funding) into diplomacy and development assistance at a time of growing international tension, while our military expenditure continues to rise.

Bomana War Cemetery, Port Moresby (Pinterest/John Lemos)

Bomana War Cemetery, Port Moresby (Pinterest/John Lemos)

It is difficult to work out who this book is aimed at, beyond Read’s immediate family. It is, as the subtitle says, a reflection. As such, it is very personal, with many odd stylistic quirks and anachronistic usages that are distracting: Mobsby’s letters reveal his ‘headspace’; aircrew did not ‘eject’ from B-25s; ‘media spin’, no matter how effective, was unlikely to conceal the superiority of the Japanese Zero from the pilots facing them. The book’s examination of history is at times superficial.

Were my teenage grandson to start asking the same questions that Read asks, I don’t think I would direct him to this book as his first or best introduction. However, readers who prefer to approach complex issues through the perspectives of an individual’s search for understanding, rather than through ‘boffiny tomes’, will find it engaging.

[*] Derek Abbott is a retired Senate officer. He has done reviews for Honest History on the 1942 Melbourne ‘brownout murders’, what-ifs in history, the Commonwealth today, Monash and Chauvel, Australian home defence in World War II, the Silk Roads, Victor Trumper, sport, Australian foreign policy, World War I at home, Duchene/Hargraves and the discovery of gold, Charles Todd of the Overland Telegraph, and other subjects.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.